A Tribute to Pádraic Ó Conaire

A Tragic End to a Prolific Life

Despite being born into relative affluence, Pádraic Ó Conaire died alone and destitute in the paupers' ward of Dublin’s Richmond Hospital on October 6th, 1928, at the premature age of just forty-six. Over the course of his life, he produced a remarkable body of work—473 short stories, 237 essays, six plays, and a novel—all written in Irish. He was awarded ten Oireachtas na Gaeilge literary prizes over a span of nine years and is regarded as one of the founding fathers of the Irish language revival, spearheaded by Connradh na Gaeilge—a movement that continues to this day.

Formative Years

One of five children of Tomás Ó Conaire, a publican, and his merchant wife, Cáit (née Ní Dhonncha), Pádraic was born on February 28th, 1882, in the Lobster Pot Bar—a public house owned by his father near the docks in Galway town. In addition to the bar, the Ó Conaires operated a provisions and general merchant store selling foodstuffs and household goods. Within a few short years, however, Tomás was forced to emigrate to America in 1887, following an economic downturn and the collapse of his businesses. He died just a few months later in Boston, on March 16th, 1888, after contracting typhoid fever, and was buried in Mount Calvary Cemetery in Roslindale, according to Massachusetts town and vital records. Adding to the tragedy, Ó Conaire’s mother passed away suddenly in January 1894 in Galway, of unknown causes. Orphaned at the tender age of eleven, Pádraic and his siblings were partly raised by relatives in Ros Muc, a village in Galway’s Connemara Gaeltacht, and in west County Clare. Although both parents spoke Irish, they raised their children as English speakers. It was only during his later upbringing by relatives that Ó Conaire developed a love for the Irish language and began speaking it fluently.

Education and early career

In 1898, Ó Conaire attended Rockwell College near Cashel, Co. Tipperary, later transferring to the prestigious Blackrock College in South Dublin, where he was a classmate of Éamon de Valera, the future President of Ireland. However, he left

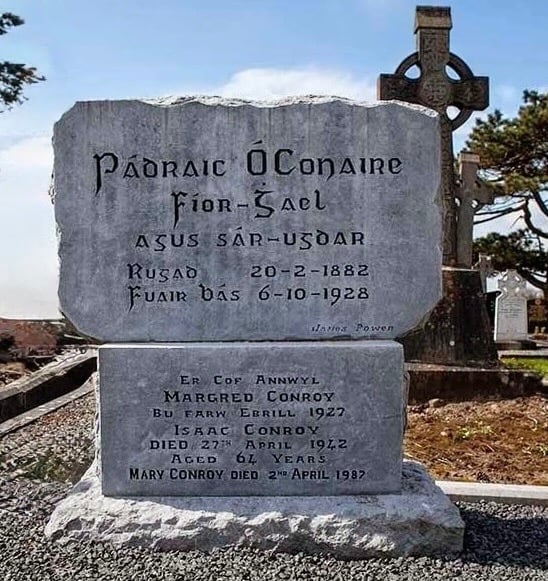

Final resting place, Bohermore Cemetery, Galway

school abruptly before completing the Intermediate Certificate Examination (Secondary Education), and emigrated to London in 1899, where he secured a junior position in the Civil Service as a boy copyist for the Board of Education. While in London, he joined Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League), whose primary objective was—and still is—to promote Irish as the standard language of Ireland. Under the influence of Irish writer and scholar Liam P. Ó Riain, as well as the poet Tomás Ó Buí, he became an accomplished Irish-language teacher and author. Less than two years later, in 1901, he published his first short story, An t-Iascaire agus an File (The Fisherman and the Poet), in An Claidheamh Soluis (Sword of Light), an Irish nationalist newspaper.

Literary Influences and Political Ideals

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ó Conaire did not draw primarily from the Irish folk storytelling tradition. Well-educated and unusually literate for his time, he portrayed an Ireland that stood in stark contrast to the stereotypical, sentimental version often found in contemporary writing. He was deeply influenced by the modern realism of French writers Balzac and Maupassant, and by Russian masters including Chekhov—whose stylistic restraint shaped his prose—and Dostoevsky, whose moral complexity in characterisation resonated strongly with him. The writings of Tolstoy and Gorky further broadened his worldview and deepened his thematic vision. A committed nationalist, Ó Conaire joined Óglaigh na hÉireann (the Irish Volunteers), established in 1913, and played a prominent role in the Irish cultural revival, working tirelessly as an Irish-language teacher and writer in both England and Ireland.

A Voice for the Marginalised

Drawing on his own experiences growing up in the Gaeltacht of western Ireland and his years spent in London as an expatriate and immigrant, Ó Conaire developed a deep empathy for those on the margins of society. His emotional insight and perceptive understanding of human nature allowed him to portray characters with uncanny realism. He used this gift to great effect in his timeless stories, which vividly capture a bygone era in Irish history. His focus was often on the blue-collar and rural poor—people trapped by poverty, tradition, and social repression in early 20th-century Ireland. Other recurring themes in his work include the enduring conflict between rural and urban life, and the issue of emigration, which caused deep social devastation in Ireland, splitting families apart over generations. Ó Conaire experienced this firsthand, as his own father left Galway for America in 1887—never to return—when he was just five years old.

Characters Rooted in Reality

Ó Conaire portrayed the lives of ordinary men and women grappling with the routines of daily life, depicting farmers, fishermen, spinsters, and others drawn from the small-town communities he knew so well. His characters are often unfulfilled, faltering at pivotal moments or making poor choices; yet rather than treat them as moral failures, he portrays them with empathy—as real people shaped by circumstance, misfortune, and social constraint. His vision is always compassionate, neither moralistic nor judgmental, and consistently humane.

From Prison Gates to the Polls: Ó Conaire’s Response to the 1916 Rising

By the summer of 1917, Ó Conaire had completed what is arguably his most significant work—a collection of stories titled Seacht mBua an Éirí Amach (Seven Victories of the Rising). Each short story explores the impact of the rebellion on the lives of ordinary Irish people. In June of that year, as the final prisoners from the Rising were released from British jails, Ó Conaire was in Dublin to welcome them home and to rally nationalist supporters for funds to cover the publication costs. Around the same time, he also campaigned for Sinn Féin in the East Clare by-election, where Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) was decisively elected.

Final years and Legacy

In the 1920s, Ó Conaire struggled with alcoholism and spent his final years in declining health, living mainly in Galway. During this time, he taught Irish at the Technical Institute and summer colleges, contributed articles to various newspapers, and worked on behalf of Conradh na Gaeilge. He also made periodic visits to Dublin, attending meetings in his role as Timire (Organiser), and to London, where he visited his immediate family. While Ó Conaire may not be remembered for elaborate literary prose, his storytelling remains powerful, direct, and deeply human. His greatest legacy lies in his decision to write in Irish at a time when the language stood on the brink of extinction. As both a storyteller and cultural revivalist, he breathed new life into Irish literature—not through ornamentation or embellishment, but through clarity, sincerity, and emotional truth.

Honouring a Cultural Icon

Gifted sculptor Albert Power, R.H.A., was commissioned by Conradh na Gaeilge in 1929 to create a statue of Pádraic Ó Conaire. After an extensive search to secure a suitable block of native limestone, the statue was finally unveiled on Easter Sunday, 1935, by President Éamon de Valera before a packed crowd in Eyre Square, Galway—in a fitting, if perhaps overdue, tribute. The statue quickly became a source of local pride, serving as a popular meeting place and inspiring countless photographs of tourists and locals alike. Power’s sculpture captured the essence and humility of Ó Conaire, symbolising a renewed Irish cultural identity ready to supplant the harsh legacy of British repression. Appropriately, the statue was mounted on the very pedestal where a monument to Lord Dunkellin, an Anglo-Irish MP, had once stood—before being torn down and thrown into the River Corrib in 1922. Sadly, Ó Conaire’s statue endured a checkered history, culminating in its decapitation in April 1999 at the hands of four youths from Co. Armagh during a night of drunken vandalism. The men were arrested the next day while fleeing Galway on a bus—when the head of the statue rolled out of a plastic bag on the floor. Damages were estimated at £50,000, and the vandals were subsequently charged with criminal damage. The presiding judge remarked that "the attack had as traumatic an effect on Galway as the Mona Lisa being taken from the Louvre in Paris". Vandalism over the years,—as well as the famous visit of U.S. President John F. Kennedy—led to the statue being moved a total of four times. The original sculpture, restored by Galway sculptor Mick Wilkins, now resides in Galway City Museum. In 2015, a bronze replica was commissioned by the city council and now stands once again in Eyre Square—a permanent reminder of the contributions of this extraordinary man who left an indelible mark on Irish history.

An Enduring Voice of Ireland

Ó Conaire’s writing, though often stark, is never without grace. His themes—poverty, emigration, vagrancy, alcoholism—reflect the grim realities of his time, yet his economy of language and frequent use of abrupt, unresolved endings lend his stories a haunting resonance. A masterful raconteur, he wrote with honesty and restraint—qualities that continue to echo in his works to this day.

—Richard A. Cullen

“Ní hé an stíl mhaisiúil is aoibhne liom, ach an stíl atá fíor.”

“It is not ornate style that I love, but the style that is true.”

— Pádraic Ó Conaire